No products

Prices are Management included

Why running shoes do not work: pronation, cushioning, movement control and running barefoot (III)

Third and final part of the translation and adaptation of the original article written by Steve Magness, coach at the University of Houston (USA)

You can find the two previous parts in these links: Part 1, Part 2

Running barefoot?

As usual, this topic could not be complete without a brief mention of running barefoot.

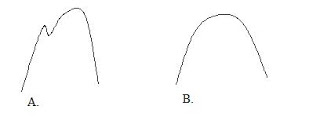

An interesting fact to note is that the maximum initial impact force is absent when running barefoot compared to running in trainers. In the graph we can see this: (A) for shoes and (B) for bare feet; that small peak in the curve of the impact force at A is the initial impact force. There is a hypothesis that this initial impact force is related to injuries.

In research by Squadrone et al. (2009), they compared cushioned trainers, running barefoot, and doing so in the minimalist Vibram Fivefingers. It was shown that impact forces, ground contact time and stride length were reduced, but stride frequency was increased when running barefoot (and in the Vibram Fivefingers) compared to running in traditional cushioned shoes. Although these results are not unexpected, they show that running shoes alter our natural stride.

An interesting point is the reduction in stride length and the increase in stride frequency. Shoes tend to promote this longer step leading to increased contact times and frequency, and this happens due to changes in the perception of feedback. As a result, the likelihood of landing with the leg extended and on the heel, carrying all the weight, is increased; it is interesting to note that elite runners have short contact with the surface and their stride frequency is high.

In these barefoot running theories based on sensory information, it has been found that there is a greater degree of stiffness in the lower leg. This may be due to the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC), which results in greater force in the "push off" or take-off of the delayed leg. In relation to this, Dalleau et al. (1998) showed that muscle pre-activation causes increased stiffness and improves running economy; in their study, the energy cost of running was related to leg stiffness.

Another recent study found that "knee flexion torque" and "internal hip rotation torque" were significantly higher compared to running barefoot. What does all this mean: potentially, this means more pressure on the joints in this area. Jay Dicharry expressed it best when he said:

"The soft, thick materials in modern cushioned running shoes allow a type of contact that would not be made in bare feet, and the foot no longer receives the proprioceptive signals it used to have by not fitting quickly to surfaces. This can silence or alter the feedback the body receives during the race and result in a runner adopting a mode of running that causes impact forces to increase.

The only issue that anti-barefoot/heel strikers raise against barefoot/midfoot strikers is that of the Achilles tendon. It is said, with good reason, that the load placed on this tendon is much greater in runners who impact with the midfoot. In view of this, it is enough to analyse the powerful tendon and realise that it is designed to carry a great load (it is the largest and most powerful in the human body); the problem is that we have weakened this tendon thanks to the use of high-heeled shoes for many years. The paradox is that, in essence, we have created the problem with the Achilles tendon by wearing shoes invented to avoid it.

The Achilles is designed to work like a large rubber band: during impact - braking or contact phase - it accumulates and conserves energy, and during the take-off phase of the race it releases it. In addition, it can store and return approximately 35% of its kinetic energy (Ker, 1987), and without this elastic storage and the consequent release of energy, the oxygen consumption required would be 30-40% higher! Therefore, and speaking in terms of performance, why are we trying to minimize the contribution of the Achilles tendon in the movement made during the race? It is like wasting an enormous amount of energy.

Cushioned running shoes do not use this energy storage and return as they do when running barefoot or in minimalist shoes, in fact more energy is lost with conventional running shoes than when running barefoot (Alexander and Bennett, 1989). In addition, in some models of cushioned shoes, the plantar arch is unable to act as a spring; this important part of the foot can store about 17% of the kinetic energy (Ker, 1987). Considering these results, it is not surprising that running barefoot compared to running in cushioned shoes is more efficient. Several studies have shown a decrease in VO2 at the same rate when running barefoot, even when weight is taken into account. This should not be too surprising since as mentioned above, without the elastic recoil of the Achilles tendon, the need for VO2 would be 30-40% higher. Running in minimalist shoes allows a better use of this energy system.

Therefore, the message to be extracted is that cushioned shoes that cause mechanical changes in the natural way of running, are not optimal for fast running, since they produce: decrease in the frequency of stride, increase in contact with the surface, decrease in the rigidity of the system, decrease in the elastic contribution, and so on.

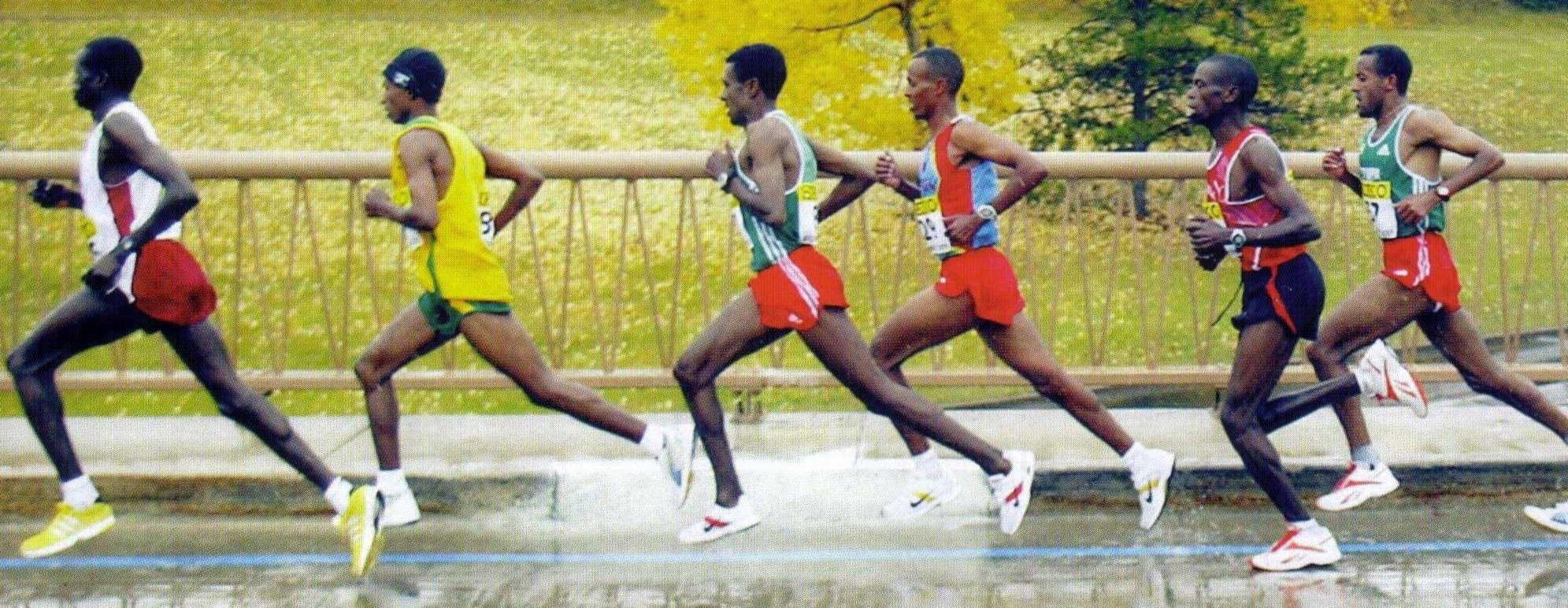

Summarizing through the "elites":

By observing elite athletes when they run, they usually have a high stride frequency, a minimum contact time with the ground and a landing very close to their centre of gravity. Since most of these "elite" runners exhibit these same characteristics, it makes a lot of sense to regret that this is the best and fastest way to run. So why are we wearing shoes that are designed to increase ground contact or that promote stride landings in front of the body's centre of gravity?

Conclusion:

In conclusion, I am not saying as a fanatic that we should get rid of all the shoes right now, since the reality is that we have probably been running in a certain way for many years. Our bodies require an adaptation that will have to be done little by little if we want to undo everything we have learned so far.

The purpose of this article is not to talk about the benefits of running barefoot but to point out the problems with the current classification system of running shoes: the cushioning/pronation issue is not as true as we are led to believe. This concept needs to be re-evaluated as it is not based on "good science" but rather the initial ideas that made sense without science supporting them, but the subsequent revision is the key test.

A recent study found that the use of the old shoe classification system, which everyone uses, had little influence on injury prevention in a large group of army participants (Knapik, 2009). They concluded that shoe selection based on arch height (as all major shoe magazines and analysts continually suggest) is not necessary if injury prevention is the goal. I guess this means that such a classification system is "broken".

Where are we going and how can we fix it? I have no idea. I'm sorry but there are no great answers. I'm inclined to suggest that our goal is to let the foot work as it is meant to, or at least wear some shoe that, by altering the mechanics of the foot slightly, still allows for good feedback. The first step in achieving this is to review and reassess the foundations on which running shoes are built: movement control, stability and cushioning.

I'll end with something I've already said, but which is an important concept:

The body is more complicated and more intelligent than we think: the shoe modifies the way we run, and it's not due to the change of alignment of the leg or the cushioning, but to the alteration of the sensory feedback. The brain is a wonderful thing.

Dejar un ComentarioDejar una respuesta

Blog categories

- Running Technique

- Shoes Review

- Scientific studies

- Nike and minimalist shoes

- Morton neuroma

- Bunions

- Podiatrists' opinion on...

- Claw toes, crowded toes,...

- Flat feet

- Runner's injuries, runner's...

- Sprained feet, ankle sprains

- Footwear for wide feet or...

- Heel and back pain

- Children's feet and...

- Circulation and bone...

- Knee pain, osteoarthritis,...

- Plantar fasciitis

Últimos Comentarios

Antonio Caballo

Feet that are not feet and that's why they hurtCristina Schmitt

Feet that are not feet and that's why they hurtAntonio Caballo

Is Barefoot expensive? you will see that Yes